It seemed so over.

After scorching instant classics like Pulp Fiction, Clerks, and Slacker into American consciousness, Sundance had burned itself out.

Independent film had shed its radical aesthetic. Instead, it draped itself in the trappings of prestige, churning out “glossy, classy and thoroughly nana-pleasing” fare like The Full Monty.1 Even Miramax, once the crown prince of counterculture, had embraced the cinematic equivalent of a four-bed in the suburbs, its output bursting with respectable awards bait, from Shakespeare in Love to The English Patient.

In 1998, Peter Biskind published Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, his warts-and-all retelling of the rise and fall of 1970s New Hollywood — the marijuana-stained, coke-fuelled, acid-soaked era of The Godfather, of Chinatown, of Altman, Ashby, Friedkin and Bogdanovich.2

In the book’s mournful closing sections, Biskind concluded that American filmmaking might never again reach such dizzying heights.

But, just one year later, everything changed.

Biskind was wrong.

Movies were back.

In 1999, America witnessed what Best. Movie. Year. Ever. author Brian Raftery describes as “the most unruly, influential and unrepentantly pleasurable film year of all time.” For a glorious moment, American cinema threatened to rival — and perhaps even surpass — the New Hollywood heights.

This was the year of The Matrix.

Of Fight Club.

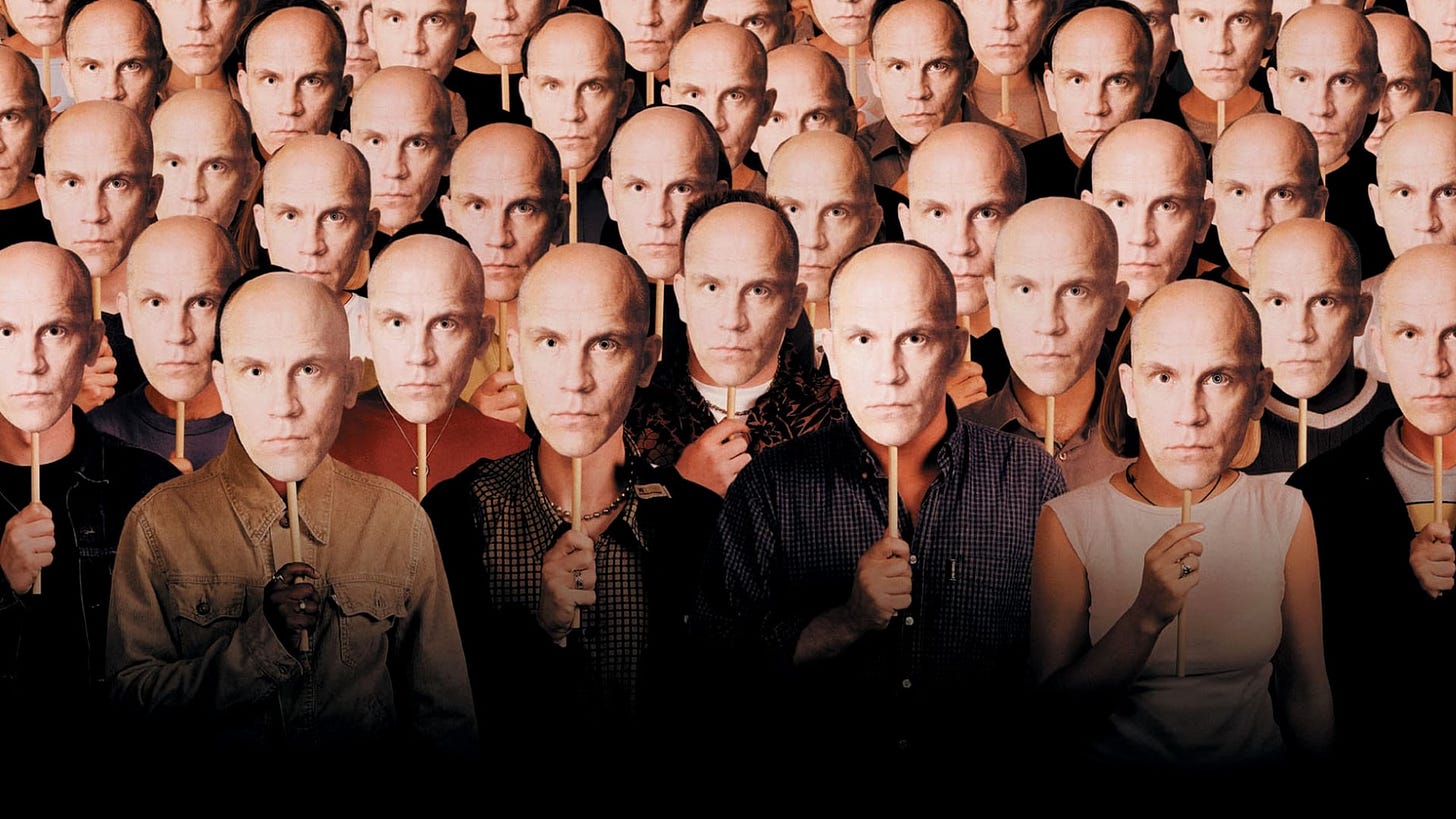

Of Rushmore, Election, Eyes Wide Shut, American Beauty, and Being John Malkovich. Of The Sixth Sense, Magnolia, The Insider and The Best Man.3

In Easy Riders, Biskind had savagely dismissed 1980s and early 1990s Hollywood as an era of impersonal, sanitised, focus-grouped blockbusters. Now, it seemed like this had been nothing but a bad dream — or, in the vernacular of one of 1999’s greatest hits, a simulation.

Like Biskind, Raftery offers an effortlessly entertaining account of a halcyon era. Like Biskind, Raftery writes from the perspective of someone looking back wistfully at what we may have lost. But while Biskind approached his subject as a pathologist might a cadaver — picking at its carcass to identify what delivered the final blow —Raftery's approach is more celebratory, reliving the glory days before they’re lost to history.

While Biskind chronicled how the New Hollywood died, Raftery asks a different question.

How did 1999 live?

Teetering on the precipice of the millennium, 1999 was a year torn between reverence and reinvention. “The past was everywhere you looked,” says Raftery. “As if all of those previous cinematic epochs had been compressed, burned onto a zip drive, and passed around from one filmmaker to the next.”

While New Hollywood had toppled its old guard, 1999 witnessed the resurrection of directors who had made their bones in previous decades. Cinema loves a comeback, and 1999 delivered the return of Scorsese, Lucas, Malick, Mann, Lynch and Kubrick (with varying degrees of success).

But it was the apprentices, not the masters, who defined the year.

This new generation — predominantly men and women in their 20s and 30s — were students of Scorsese, acolytes of Friedkin. They sought to capture not the Great Men’s style or subjects but their “unvarnished, unfulfilled sense of purpose-driven ennui.” Like their spiritual ancestors, these filmmakers set out to tell personal, confessional stories that resisted the four-quadrant analysis of studio production.

But this was 1999. Twenty years of blockbuster filmmaking, coupled with technological developments once consigned to science fiction, had left their imprint. These were as much children of Cameron and Lucas as they were of Altman and Beatty. What emerged were a series of “sneakily personal” films that welded 1970s-style introspection with the techno-charged, big-budget sensibilities of the era, “luring viewers with promises of high-end thrills or movie star grandeur— only to turn the focus back on the audience.”

This bionic blend of auteurist vision and multiplex spectacle was partly enabled by technology, which was infiltrating not just how films looked and felt but the very fabric of storytelling. Digital editing, affordable equipment, and a thriving home video industry that enabled repeat viewings and frame-by-frame analysis meant that filmmakers “ripped up and remixed the century-old rules of cinema, screwing with time, perspective, and expectations.”

Television, too, was beginning to bear its influence, not least via shows like Cops and other real-world docudramas that, Raftery argues, had introduced a new “narrative form,” one much looser and more mobile, one where “the camera zipped and zoomed, almost as if it was self-guided, to focus on whatever image was the most urgent.”

An explosion of narrative experimentation followed. The nonlinear recursiveness of Run, Lola, Run. The cross-cutting chronological shenanigans of Nolan’s Following. The fragmented memory of Soderbergh’s The Limey. The handheld verité of The Blair Witch Project. Even films built upon traditional Hero’s Journey structures — The Matrix, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace — harnessed technological developments to create vast, immersive new worlds and unlock visually mind-bending possibilities in the one we already inhabit.

But you can’t spell “big-budget auteurism” without “auteurism,” and while technology unlocked 1999’s grandest spectacles, the real pyrotechnics were of the intellectual variety…

1999 was a Big Bang moment for directors with something to say. These filmmakers weren’t content with merely wielding their new technological toys. Instead, they used them to unleash their point of view and ideas upon audiences.

Just as Biskind saw New Hollywood as a cultural rebellion against the play-it-safe studio era of the 1950s, Raftery argues that 1999 represented an uprising against the hollow, facile blockbusters of the 1980s and early 1990s. He quotes Fight Club director David Fincher, and Boys Don’t Cry director Kimberly Peirce:

Fincher: “Speed was one of the biggest movies that had ever been made at that time—but was [director] Jan de Bont a voice? No. These directors we’re talking about all have something that stains what they do.”

Peirce: “A bunch of us were reacting to the bigger and more actiony movies of the nineties, saying, ‘That’s not how I think—but I have this story that I really love, one that’s smaller and weirder.’ ”

That cinema could mount such a collective response is telling. As Raftery puts it, “film culture was popular culture.” Movies weren't just in conversation with each other—they were responses to the zeitgeist itself.

Before society fragmented into countless digital bunkers, the counterculture could still speak with one voice. And in 1999, it had a lot to say.

Great hope — of history’s end, of technological liberation, of unheralded prosperity — was tempered by great anxiety. Y2K fears were both a symptom and a cause, a signal that, come the millennium, all bets were off. Something was looming, something unpredictable, something revolutionary. There was a sense of “confusion and unease,” Raftery suggests, a fear that “things were going a bit too smoothly.” America was “hurtling toward something,” but that something remained up for grabs.

Out of this existential angst emerged a suite of films that, like cultural white blood cells, confronted the hostile elements in their ecosystem.

The smoothing, soothing, oppressively ubiquitous effects of technology and bureaucracy were a primary target. A sense of unfulfilled emasculation was beginning to take hold. How could one live in a world where there is nothing to fight for? How could people — usually men — neutered by their jobs, by their very culture, fight back? A wave of films gave voice to this frustration. Neo’s escape from the Matrix. Pete’s ‘I don’t care’ transformation in Office Space. The human puppetry of Being John Malkovich. The vandalistic debauchery of Fight Club.

Office-based dissatisfaction fused with growing domestic unease. This was a generation born of the early eighties divorce spike and raised on tabloid tales of adultery. From Eyes Wide Shut to Varsity Blues to American Beauty, movies were “rife with domestic warfare” as filmmakers challenged comfortable myths of domestic bliss. African American audiences and filmmakers were also growing tired of established narratives, particularly cinema’s relentlessly bleak portrayal of hood culture. In 1999, films like The Best Man and The Wood responded with nuanced perspectives that looked beyond the inner city.

Of course, filmmakers having something to say was only half the picture. The real surprise was how willing studios were to let them say it.

The New Hollywood era had emerged from a studio system on its knees. Desperate for hits, the studios made their Faustian bargain, hitching their fortunes to a cinematic movement they could neither control nor understand.

Raftery is less interested than Biskind in industry minutiae. Yet one thing is clear: by 1999, studios weren’t just reluctant sponsors but eager participants in cinema’s new wave.

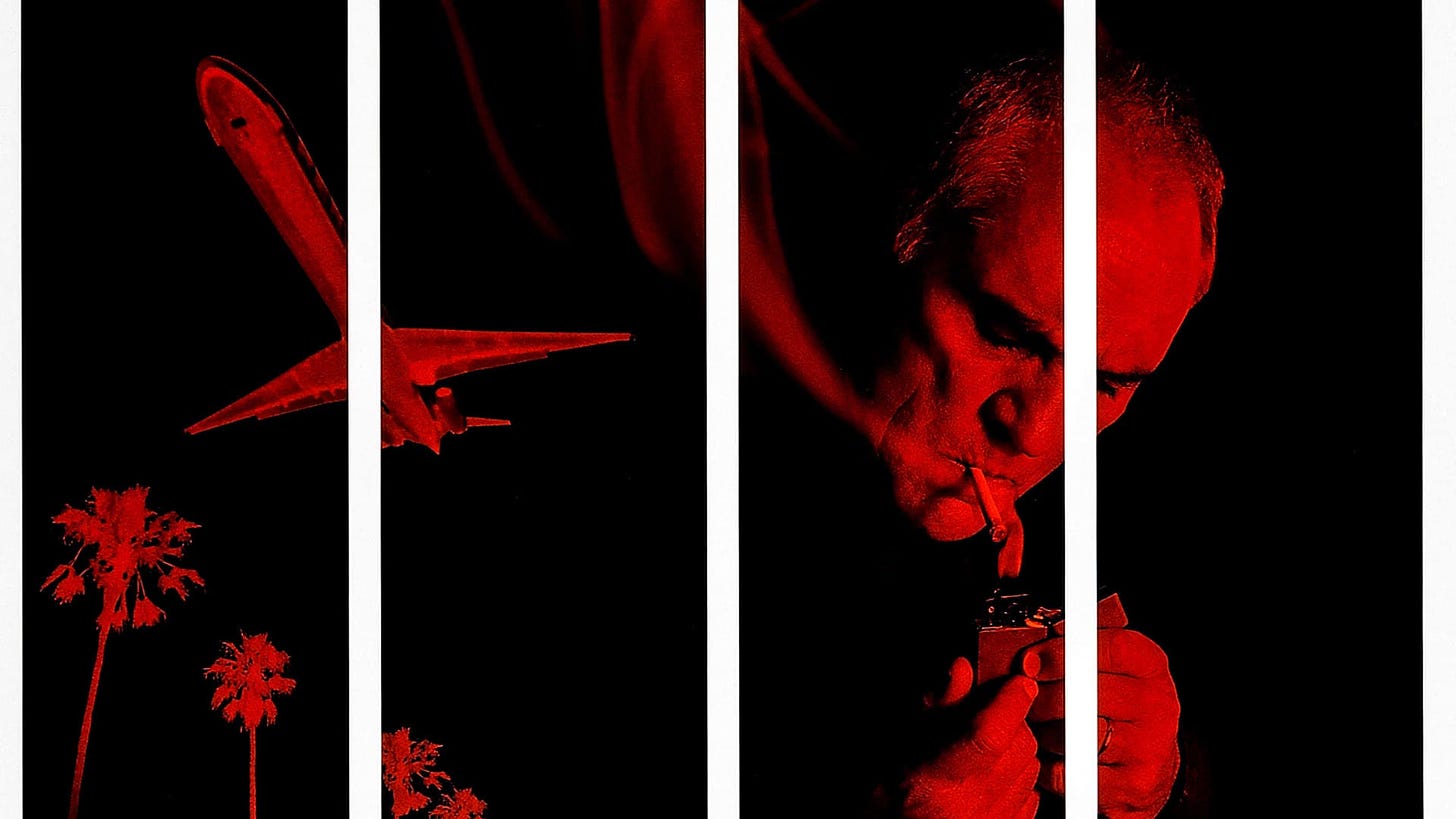

Audience fatigue was setting in. The studios "had watched moviegoers grow increasingly tired of unsolicited remakes and retreads,” writes Raftery. “They wanted new adventures, new ideas.” Hungry for hits, they threw bucketloads of cash at auteurist swings like The Insider ($68 million, Disney(!)), Fight Club ($65 million, Fox), Eyes Wide Shut ($65 million, Warner Bros), The Matrix ($60 million, Warner Bros), Magnolia ($35 million, New Line) and Three Kings ($50 million, Warner Bros).

The great splurge of studio dollars reflected and fuelled what was already being hailed as a halcyon era for screenwriters. As Steven Soderbergh told Raftery, the studios were “riding a wave of talent.” Throughout the 1990s, writers like Shane Black had emerged from their dusty, candlelit cocoons to become celebrities in their own right. The spec script market was soaring, and original, madcap screenplays — Being John Malkovich, Go, American Beauty — were devoured by the hungry studios (some executives even read scripts for pleasure).

This fertile market emboldened young writers and directors, who dared to believe they could make the movies they’d always dreamed of. Raftery quotes The Wood director Rick Famuyiwa:

“For a first time filmmaker, the nineties felt wide open […] there was still this notion that the studios wanted to find original voices and original ideas.”

Not every big swing connected immediately. Many films we now consider unqualified successes — Rushmore, Fight Club, Office Space, Election, The Virgin Suicides — stumbled out of the blocks. But a new trend was emerging. The DVD era had arrived, allowing these films and more to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat, paving a post-release path to immortality.

DVDs represented the last hurrah of the analogue age. But even as copies of Fight Club (which had been critically and commercially panned), The Matrix and Rushmore were being proudly played and displayed in the dorm rooms of college students up and down the country, the fledgling digital era was beginning to stretch its muscles…

The internet held great promise. Not yet woven into the fabric of society, it remained a tool to be wielded rather than a force to be surrendered to.

It was the internet that enabled the last-gasp rescue of Brad Bird’s animated classic The Iron Giant. Facing the guillotine at a struggling Warner Bros, the film gained a surge of support following a hearty online endorsement from writer Drew McWeeny. Later, to market the film, Warner Bros released a section of it online, an early harbinger of a now common industry practice.

But it was The Blair Witch Project that truly revealed the web’s potential. The famously low-budget flick was pricier on the back end — nearly $15m was spent on a legendary viral marketing push. This campaign merged analogue tricks (missing posters for the cast and pre-summer college screenings in crusty old theatres) with digital chicanery: declaring the cast dead on IMDB, an amateur-feeling website and sneaky manipulation of message board conversations. The results spoke for themselves: Blair Witch ended up making over $100 million at the box office.

But the internet’s early promise was beginning to sour. Something dark was stirring.

In Biskind’s Easy Riders, 1970s audiences were largely passive consumers, feeding on whatever the movie industry served them. Pre-Jaws, they were hungry for New Hollywood delicacies, but as the decade went on, they became addicted to less nutritious fare.

Raftery adds a new dimension. 1999 was the dawn of Nerd Culture — a new model of possessive fandom that would go on to dominate film discussion. Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, particularly the much-maligned Jar-Jar Binks, provided an early target for this emerging force as emboldened keyboard warriors indignantly claimed righteous ownership over their beloved franchise. Raftery frames the emerging fandom as an Empire-level threat:

“Only a few years after the arrival of Ain’t It Cool News, the web was filled with preemptive critics who would look at a lone leaked costume photo or read a secondhand review of a trailer and immediately declare BEST. MOVIE. EVER. or WORST. MOVIE. EVER. with a single post. Fans had grown more powerful than one could possibly have imagined, their online fiefdoms growing larger and more vocal each year.”

Although Raftery spends most of the book on 1999’s high points, this brief detour into one of its most lasting legacies is an early warning. Like Biskind before him, he is preparing to deliver his subject its killer blow.

From beginning to end, the incoming demise of New Hollywood hangs over Biskind’s Easy Riders like the sword of Damocles.

Raftery’s execution is swifter, more efficient, but no less brutal.

1999 was not 1971. It was not the dawn of a new era. Instead, it was the peak: fleeting, transitory, glorious.

In a painful few paragraphs, Raftery charts Hollywood’s post-1999 descent. As budgets skyrocketed, “megamovies” needed to land with ever-widening pools of audiences, meaning they ended up saying “as little as possible.” A push for global markets resulted in flattened stories stripped of nuance. Risk-taking became financial poison, and major studios desperately reached for safe, controllable stories. A desire for huge grosses squeezed out the middle-budget features.

Worst of all, audiences lost interest in provocative stories, instead going to movies seeking comfort at best and lobotomisation at worst (if they even went to the movies at all).

It's a grim read. Published in 2019, there’s little evidence that these trends have slowed down.

Yet, while Hollywood big-budget filmmaking may have hit its nadir, green shoots are emerging.

If you read my New Hollywood essay, you’ll notice how Raftery’s criticisms echo those of Biskind in Easy Riders. The irony is glaring. Two decades after Biskind declared the death of cinema in 1998, Raftery celebrates 1999 — the very next year — as a cinematic high point, all while applying Biskind’s criticisms to contemporary Hollywood.

Perhaps we movie lovers are doomed to this cycle, to overlook the quality surrounding us while yearning for some idyllic past.

2007 — the year of Zodiac, There Will Be Blood, No Country For Old Men, and Michael Clayton — has already been canonised as a year to rival the greats, a dark, post-9/11 mirror to the wide-eyed futurism of 1999.

But we needn’t reach that far back.

Look at 2019: Uncut Gems, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Parasite, The Irishman, Midsommar, The Lighthouse, Marriage Story.

Or even 2023: Oppenheimer, Killers of the Flower Moon, Past Lives, The Zone of Interest, May December, Asteroid City.

Perhaps the lesson is that great movies surround us if we only have the eyes to see them. After all, how many people who claim that ‘movies are rubbish now’ actually go to the cinema regularly?4

Yes, big studios remain addicted to sequels and superhero slop (I say this as a card-carrying fan of Marvel’s Infinity Saga). But even here, hope stirs.

1999 emerged from a perfect storm of factors — anxious but ambitious filmmakers with something to say, audiences eager for fresh stories, and studios, shaken by formulaic flops, ready to gamble on originality.

Are we seeing something similar today? The calamitous failure of Joker: Folie à Deux may give studios a sobering lesson that not everything deserves a sequel. Deadpool & Wolverine aside, Marvel has failed to reclaim its 2019 cultural dominance. Meanwhile, original movies like The Substance, It Ends with Us, The Wild Robot, Longlegs, and Anyone Like You have found surprising success. Perhaps audiences genuinely are ready for something different.

Towards the end of The Matrix, Neo declares: “I don't know the future. I didn't come here to tell you how this is going to end. I came here to tell you how it's going to begin.” Perhaps in twenty years, when the next Raftery or Biskind looks back at our era, they won’t see it as cinema’s nadir but as a new beginning — the moment everything changed. Again.

If you enjoyed this essay, you will love its predecessor, How the New Hollywood Died. Or, if you fancy something a bit shorter, here’s a palette cleanser for you: Why Does Editing Work?

If you didn’t like what you’ve just read, what are you still doing here!

Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes in this essay are taken from Brian Raftery’s Best. Movie. Year. Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen.

I wrote about this book at length here: How the New Hollywood Died.

So spoiled for choice was Raftery that The Talented Mr. Ripley, Bowfinger, and Toy Story 2 barely get a mention.

This is very fascinating, thank you for sharing! I believe that indie cinema is in a cyclical peak of quality and originality (perhaps beginning with Robert Eggers' The Witch in 2014, A24's first film) and that we are due for a dip very soon. Here's hoping the major studios learn from it, or not - either way, I'll continue to seek out indie films over big blockbusters

I do indeed those wonderful days of 1999, just banger after banger, week after week.

I think what frustrates me about executives today is that obviously they go on, over and over again, saying IP, IP, IP. And that makes sense from a business perspective. But you need to develop NEW IP for that plan to work. And that TERRIFIES them.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse,substack.com