Easy Riders, Raging Bulls fills much of its 500 pages with unapologetically salacious insider accounts of the sexual, drug-fueled proclivities of some of the most revered filmmakers in American history.

“Schrader took to coke like mother’s milk,” writes author Peter Biskind.1 “He plunged into the drug scene with the enthusiasm of a lapsed fundamentalist.” Robert Altman, on the other hand, “took to grass like a guernsey […] He’d get a relaxing high off weed without the nastiness that surfaced with booze.” William Friedkin’s vice was sex, not drugs: “For years I would just see hookers,” quotes Biskind. “All I was interested in doing was getting laid.”

It’s titillating stuff, reported with carnal glee by Biskind. So full-throated was his account of the New Hollywood underbelly that the book’s publication in 1998 saw him isolated as somewhat of a pariah among its subjects — “the worst kind of human being I know,” spat Robert Altman, “every single word in that book about me is either erroneous or a lie” insisted Steven Spielberg.

Yet Biskind’s enthusiasm for the raunchy reality of 1970s Hollywood isn’t the voyeuristic impulse of a tabloid hack. A film historian, cultural critic, and journalist who served as editor-in-chief of American Film magazine for five years and executive editor of Premiere for ten years, Biskind’s willingness to dwell in the sweaty, sordid details doesn’t resemble so much of a hit job as it does an excavation, an attempt to dig up the bones of a project that once held such promise to discover, 20 years later, just what led to its untimely demise.

For while Easy Riders, Raging Bulls charts a period of unbridled virility — young people creating explosive, singular art while smoking, shagging, and snorting to their hearts’ content — it is death that hangs over the era, both literal (poor Hal Ashby, whose final days constitute the book’s denouement) and metaphorical, as the creative furnace that was ‘70s Hollywood is snuffed out by the decade’s end.

Published in the late ‘90s, the book’s mournful sense of death, of hope extinguished, may have seemed premature in an era where directors like Brian de Palma, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg continued to make successful movies and where films like The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Chinatown, Easy Rider, The Exorcist and The French Connection continued to hold critical and cultural influence. But, for Biskind, the era’s enduring successes were the exceptions that proved the rule. Structurally, he argues, the business of moviemaking — and the movies that made business — never again came close to the promised land that seemed, for a brief moment in the ‘70s, tantalisingly within reach.

Biskind’s thesis is as follows: By the mid-to-late ‘60s, the lumbering, creaking studio era of Hollywood’s golden age had reached its creative and commercial nadir; its geriatric management and conservative moral conformity (think dusty old Westerns and formulaic big-budget musicals) crumbling in the face of "the civil rights movement, the Beatles, the pill, Vietnam, and drugs.” In its place emerged a group of hungry young baby boomers — usually white, usually male — who shared a distinctly ‘60s strain of iconoclasm and who devoted their free-flowing, fiercely independent artistic sensibilities to the explosion of independent cinema in France and other countries around the globe.

Under the traditional studio system, directors had been middlemen, gophers, there to fulfil the briefs of the powerful studio producers pulling the strings. No longer. Auteurism was the word of the decade, a theory borrowed from the French New Wave that argued that directors were the ultimate ‘authors’ of the films they created. Over the coming decade, self-styled auteurs — Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, Warren Beatty, William Friedkin, Paul Schrader, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Steven Spielberg, Hal Ashby (the list goes on) — supported by a troupe of actors (Jack Nicholson, Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Dennis Hopper, Gene Hackman, Jane Fonda and the like), proceeded to oversee a Big Bang moment in American filmmaking, an explosion of personal, character-driven, provocative cinema that stuck a booze-reddened middle finger up to the tame sensibilities of the preceding era.

“It was the last time Hollywood produced a body of risky, high-quality work,” writes Biskind, “work that was character-, rather than plot-driven, that defied traditional narrative conventions, that challenged the tyranny of technical correctness, that broke the taboos of language and behavior, that dared to end unhappily. These were often films without heroes, without romance, without—in the lexicon of sports, which has colonized Hollywood—anyone to ‘root for.’”

Yet the revolution was short-lived. By the decade's end, the studio system had enacted a ruthless counterinsurgency. The lofty vision of transforming Hollywood into a sun-soaked utopia of democratic filmmaking, populated by a cornucopia of artists creating unyieldingly individual films unfettered by studio restraints, had died. In its place, producer-led studio filmmaking returned with a vengeance, empowered and determined to never again let directors off the leash.

If there is an ultimate villain to Biskind’s story, it is the business of moviemaking, embodied by the profit-minded producers and executives who managed to wrest control from the idealistic visions of the New Hollywood. “The revolution failed,” writes Biskind. “The New Hollywood directors were like free-range chickens; they were let out of the coop to run around the barnyard and imagined they were free. But when they ceased laying those eggs, they were slaughtered.”

But if the studio system is the equivalent of Star Wars’ evil Emperor, the closest New Hollywood analogy is not Luke, but Anakin Skywalker. The great power briefly held by the era’s protagonists, coupled with their human flaws and vulnerabilities, gave rise to the very thing they were sworn to destroy.

Biskind notes how, unlike many legendary directors in history — Kurosawa, Fellini, Bergman — most New Hollywood directors “burned out like Roman candles after an all-too-brief flash of brilliance.” Biskind’s explanation is simple: too much, too soon. Flush with unprecedented prestige and resources, the generals of the New Hollywood insurgency did not know how to effectively wield their newfound power. He quotes Friedkin: “Arrogance and pussy were the double-pronged temptress for guys in our position,” and Bogdanovich: “We didn’t know how to deal with success.” Both directors peaked in the mid-70s, were subsequently humbled by a string of flops, and felt their stars had burned out by the decade’s end.

The drug-fueled excesses of the era gave rise to some of its highest moments: the totemically uncompromising Raging Bull, the coke-addled genius of Paul Schrader’s Taxi Driver script, the hallucinogenic delirium of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. But it left in its wake a trail of carnage that consumed the lives of those who embraced it. Dennis Hopper, whose Easy Rider (1969) kicked off the decade, ended it at “rock bottom,” consuming “half a gallon of rum, twenty-eight beers, and three grams of coke—a day.” Robert Evans, the mercurial Paramount executive who was head of production when it produced Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Godfather (1972), Serpico (1973), and Chinatown (1974), ended the decade pleading guilty to cocaine trafficking. Biskind quotes a mournful Paul Schrader recalling his state of mind in 1982, a year which saw the release of his commercial and critical flop Cat People and the death of actor John Belushi from an overdose: “My life was completely fucked up by women and drugs and my career had gone dead.”

“Money was the solvent that dissolved the tissue of the ‘70s,” writes Biskind. His book bridges the heady artistic sensibilities of the era with the clinical business realities. “If this book had been written during the ‘70s, it would have focused exclusively on directors,” he notes. “If this book had been written in the ‘80s, when executives and producers became media darlings, it would have been about the film business. But written in the ‘90s, it tries to look at both sides of the equation, the business and the art, or more precisely, the businessman and the artist.”

Perhaps no figure better embodies this duality — businessman and artist — than Francis Ford Coppola, an aloof, imperious presence throughout the book. Coppola spent much of the decade launching a guerrilla attack on the studio system he passionately hated. He and his friend and acolyte George Lucas founded American Zoetrope in 1969, a creator-led studio to be governed by artists, not businessmen, bypassing the embarrassingly one-sided deals that filmmakers had historically been forced to cut with the mighty studios.

“Zoetrope was a break away from Hollywood,” said Lucas. “It was a way of saying ‘we don’t want to be part of the Establishment, we don’t want to make their kind of movies, we want to do something completely different.’ To us, movies are what counts, not deals and making commercial films.’”

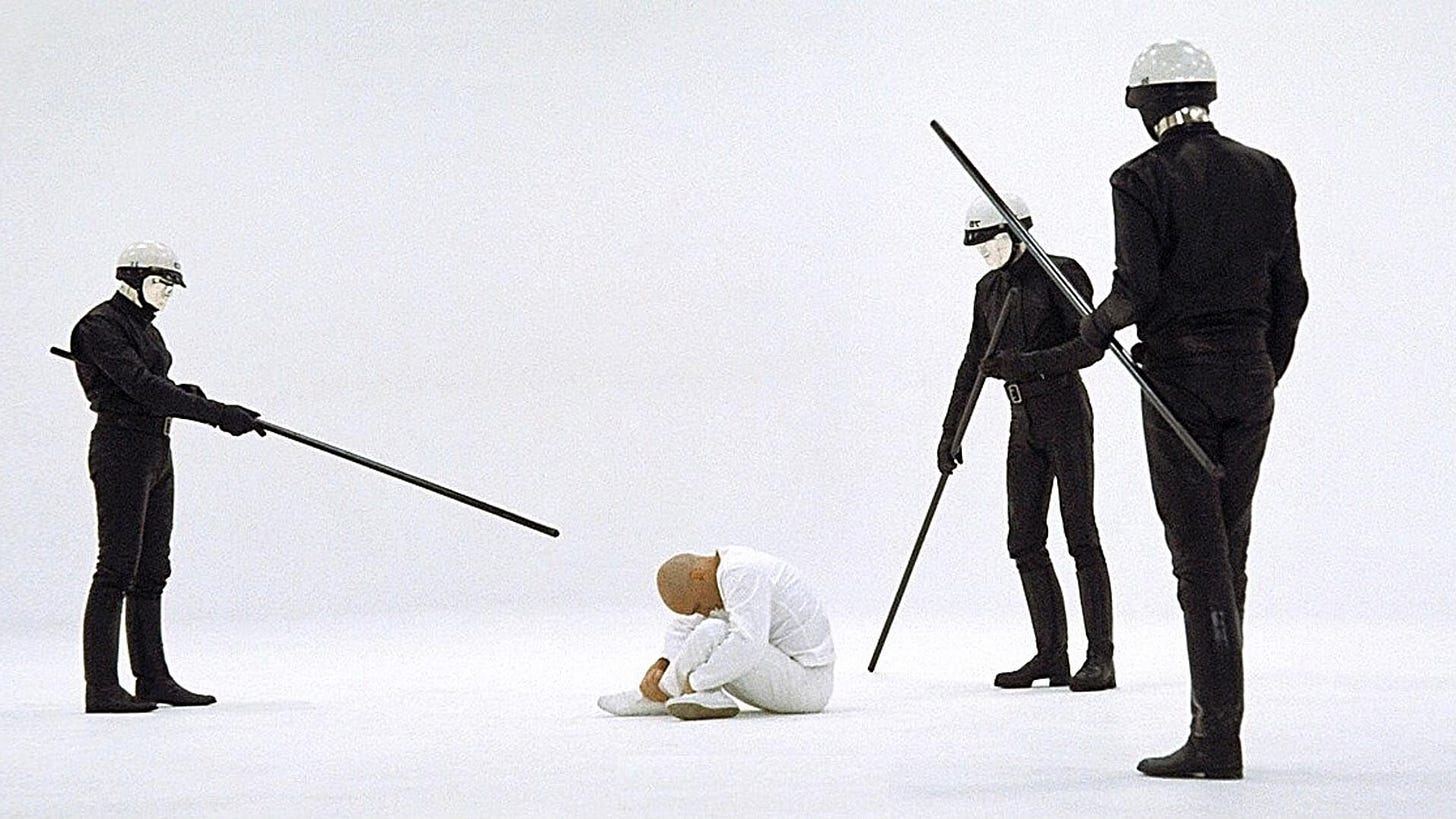

But Zoetrope collapsed in 1971, a victim of the commercial failure of Lucas’ THX 1138 and fraternal squabbling between Coppola and his partners, Ted Ashley and John Calley, two Warner Bros executives who had cut a financing deal between Warners and Coppola’s fledgling studio. To Coppola’s fury, the studio men had decided they couldn’t work with him. Zoetrope’s collapse saw Coppola on the hook for hundreds of thousands of dollars. (A fascinating turning point in Hollywood history: the failure of Zoetrope directly led to Coppola making The Godfather to earn a quick buck and prompted Lucas to move towards more commercial filmmaking, eventually leading to Star Wars).

Coppola relaunched Zoetrope in the early ‘80s with even more grandiose visions. There would be no cap-in-hand financing deal with Warner Bros this time; instead, he set it up in the heart of Hollywood as a technological utopia for artists, welcoming outsiders like Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, and Wim Wenders to make movies unbridled by studio constraints. This Zoetrope went the same way as the first one. Costs racked up, Coppola’s flagship feature, One from the Heart (1982), flopped, and Coppola’s personal financial liability skyrocketed. He filed for bankruptcy in 1982 and sold the Zoetrope lot.

Coppola was personally involved in another failed project, The Directors Company, a Paramount-backed partnership between Coppola, Bogdanovich, and Friedkin that gave the directors total authority over the films they made, provided the budgets were under $3 million. Once again, this was supposed to herald a new era of moviemaking. Once again, this failed, brought down by the corporate machinations of Paramount’s blindsided executive Frank Yablans, petty squabbling between the three directors, and the disastrous flop that was Bogdanovich’s Daisy Miller in 1974.2

Other grassroots studios fared more successfully but still failed to evolve into an institutional presence. Director Bob Rafelson and producer Bert Schneider jointly formed Raybert Studios (which became BBS when fellow producer Steve Blauner joined the party), who catalysed the New Hollywood revolution by producing the fiercely countercultural Easy Rider in 1969. Whereas the Zoetrope-Warner Bros financing deal had seen Coppola & co cede the final cut to Warners, the dramatic success of Easy Rider empowered Raybert/BBS to enter a six-film production deal with Columbia under which they would retain the final cut for all films provided the budget was less than $1m.3

BBS envisioned a Hollywood ecosystem bursting with small, personal pictures that could be produced at a fraction of the budget of traditional studio fare. Films were to be a family affair—free from arbitrary hierarchies or predefined roles, directors, writers, and actors alike would chip into each other’s projects, trading points on each other’s films and retaining a sizable financial interest in the upside.

While Zoetrope had been subject to the dictatorial authority of Coppola, who mandated a no-drugs policy, BBS was a more jagged affair. “There was no hipper place in Hollywood,” writes Biskind. “Smoking a joint with Bert and Bob, Dennis and Jack [Nicholson] was the ultimate high.” Nicholson was BBS’ in-house actor and was central to some of its most successful movies, including Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces (1970), Hopper’s Easy Rider, and his directorial debut Drive, He Said (1971). The critical and commercial success of these films, and of Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), appeared to signal that American audiences were hungry for the types of films that these self-styled artists wanted to make – a confluence of commercial and artistic reality that soon revealed itself as too-good-to-be-true.

BBS’ final film, Hearts and Minds, was released in 1974. Despite its success, nothing more came of the project. Like The Directors Company and Zoetrope, BBS had been empowered by a studio to produce seminal, era-defining films, yet had failed to turn this success into anything sustaining.

The failure of these new financial models cast a long shadow. “The basic structure of the company was valid -- perhaps ahead of its time,” said Paramount Vice President Peter Bart in 2004, speaking of the failure of The Directors Company. “It made sense for a studio to assign a portion of its filmmaking program to directors who would function with a high degree of autonomy. It also made sense to extend them a substantial piece of the gross receipts in return for a commitment to tight budgets. Indeed, several efforts to emulate this business plan have been advanced (most recently with a group that included Steven Soderbergh). Nothing, however, has ever taken shape.”

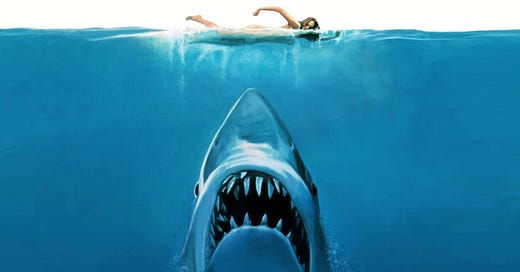

It's no coincidence that the mid-'70s was the cut-off point beyond which these fledgling projects failed to take flight. 1975 brought a film that tore the flesh from the bones of the New Hollywood revolution with the primal ferocity of its titular monster…

In Biskind’s telling, Steven Spielberg was the canary in the New Hollywood coal mine. His nervous, neurotic, shy mannerisms (“if anyone looked at him sideways, he got a nosebleed”) belied a filmmaking style that sounded the death knell for the countercultural impulses of his peers.

While the new establishment borrowed liberally from Godard, Akira Kurosawa, Federico Fellini and other titans of world cinema, Spielberg’s influences were more practical. “My influences, in a very perverse way, were executives,” said Spielberg. “I was truly more of a child of the establishment than I was a product of USC or NYU or the Francis Coppola protege clique.” Unlike many of his peers, he never held pretensions of auteurism. “He didn’t want to be the son of Jean-Luc Godard,” actor Kit Carson told Biskind. “He was just so different from Coppola and Scorsese and Schrader.” Yet the astonishing success he achieved with Jaws imprinted more of an enduring stamp on Hollywood films than perhaps any director in history.

“Jaws changed the business forever, as the studios discovered the value of wide breaks—the number of theaters would rise to one thousand, two thousand, and more by the next decade—and massive TV advertising, both of which increased the costs of marketing and distribution, diminishing the importance of print reviews, making it virtually impossible for a film to build slowly, finding its audience by dint of mere quality,” writes Biskind. “Moreover, Jaws whet corporate appetites for big profits quickly, which is to say, studios wanted every film to be Jaws.”

The blockbuster model, with huge upfront costs and an expectation of even huger, immediate profits, was up and running. So, too, was the idea that films should be reducible to a simple, core, digestible idea. Said Spielberg: “If a person can tell me the idea in twenty-five words or less, it’s going to make a pretty good movie.”

What Spielberg and, two years later, George Lucas, sniffed was the asphalt whiff of the counterculture burning itself out. Vietnam and Nixon had given audiences a taste of the dark side of America, and they didn’t like it. The comfort-blanket impulses that eventually led to Reagan’s shining city on a hill had begun to take effect. Said screenwriter Robert Towne, “A country that in LBJ’s words had truly become a helpless giant, needed a fantasy where it was not impotent, where it was as strong as Arnold, as invulnerable of Robocop.” Or, as Biskind puts it, “awe was more commercial than fear.”Audiences didn’t want sickos who reflected the country’s worst excesses. What Spielberg and Lucas ultimately offered was a cinema of hope, a cinema of universal, flat morality — of good vs. evil. Taxi Driver was many things, but it was certainly not that.

As the decade continued, the New Hollywood directors increasingly found themselves cornered between idealism and pragmatism: either embracing the breathless big-picture filmmaking audiences were after or desperately trying to hold back the tide.

Biskind portrays Coppola as constantly wrestling with the integrity of what he is doing. Amazingly from today’s perspective, even The Godfather was seen as a ‘one-for-them’ cash grab, a feeling that never completely left Coppola. “In some ways it did ruin me,” he told Biskind. “It just made my whole career go this way instead of the way I really wanted it to go, which was into doing original work as a writer-director. Basically, The Godfather made me violate a lot of the hopes I had for myself at that age.”

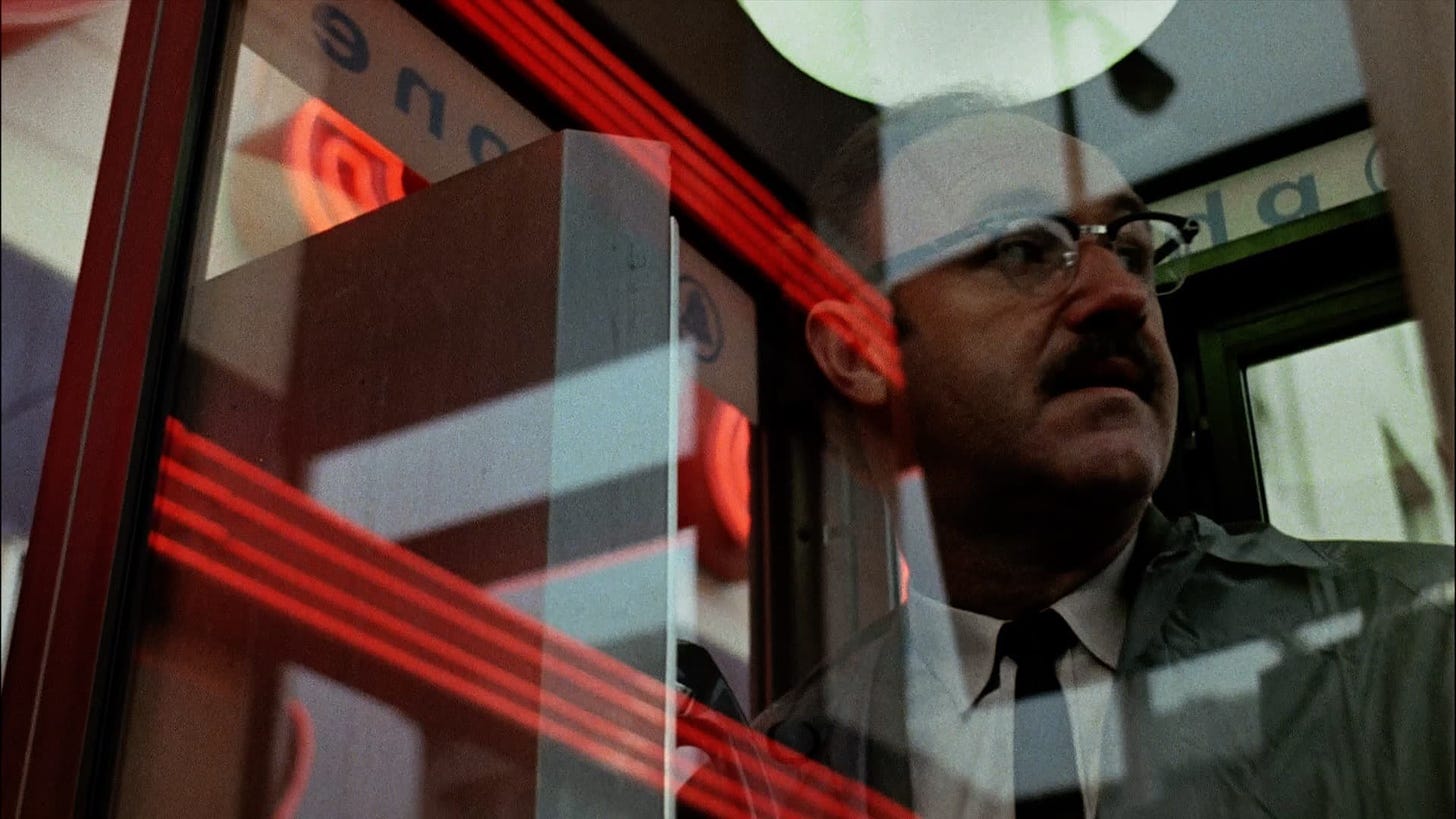

Coppola was far from the only director to be begrudgingly kowtowed into compromising his artistic integrity. William Friedkin entered the decade devoted to interpretative, plotless cinema (confidently declaring in 1967, “the plotted film is on the way out and is no longer of interest to a serious director.”) He produced a couple of art films at the beginning of the decade, before a run-in with Howard Hawks, whose daughter he was dating, made him think otherwise. “I had this epiphany that what we were doing wasn’t making fucking films to hang in the Louvre,” he said. “We were making films to entertain people and if they didn’t do that first they didn’t fulfill their primary purpose.” His next film saw him abandon his highfalutin premises - The French Connection (1971) was edited around the principle that any scenes that complexified the characters but slowed down the action could be cut.

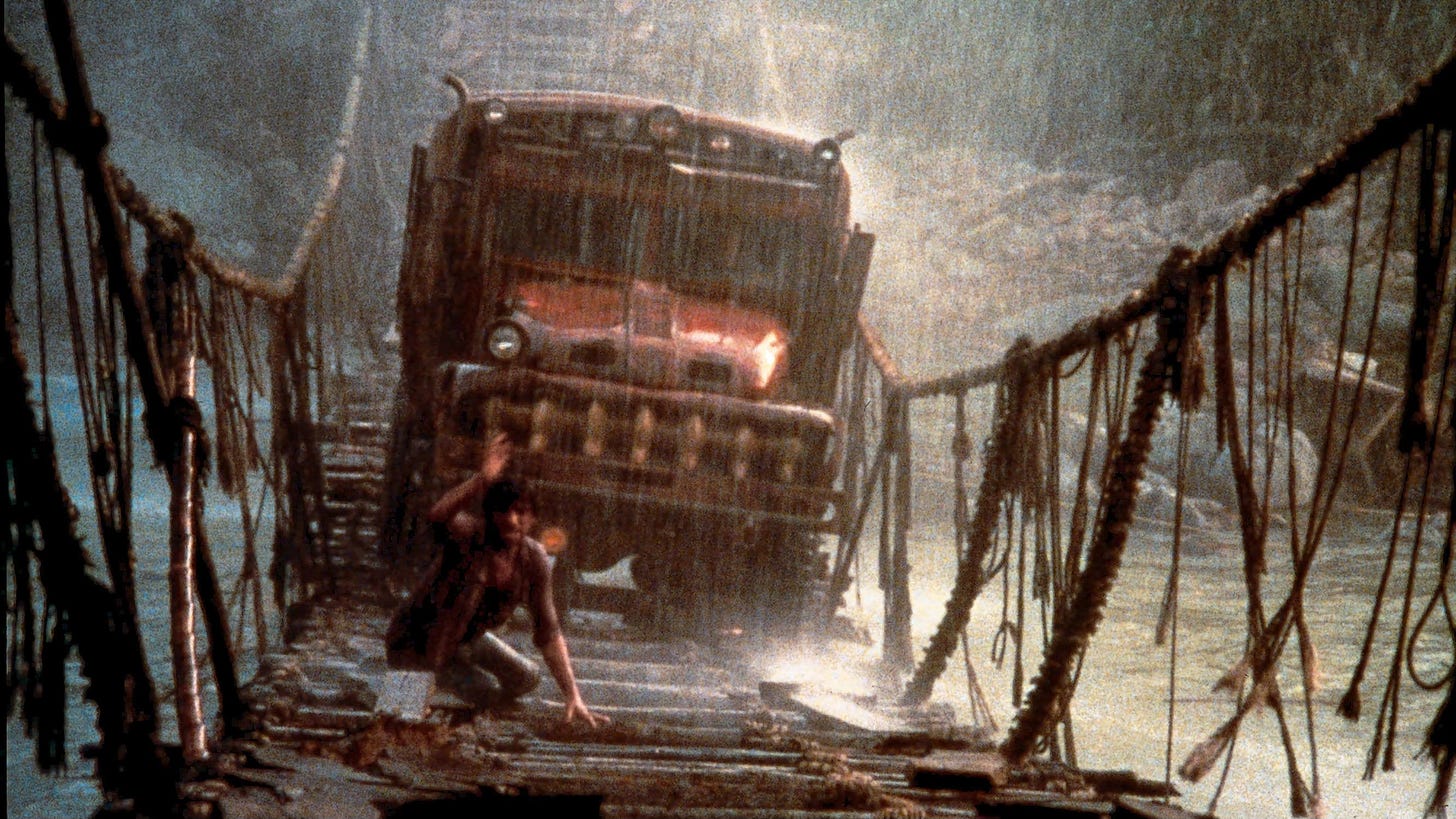

Friedkin remained conflicted between art and commerce; his decade effectively ended with Sorcerer (1977), a financial disaster that was deemed too arty to be commercial and too commercial to be arty (the film has undergone a dramatic reappraisal in the last few years and is now generally regarded as a masterpiece).

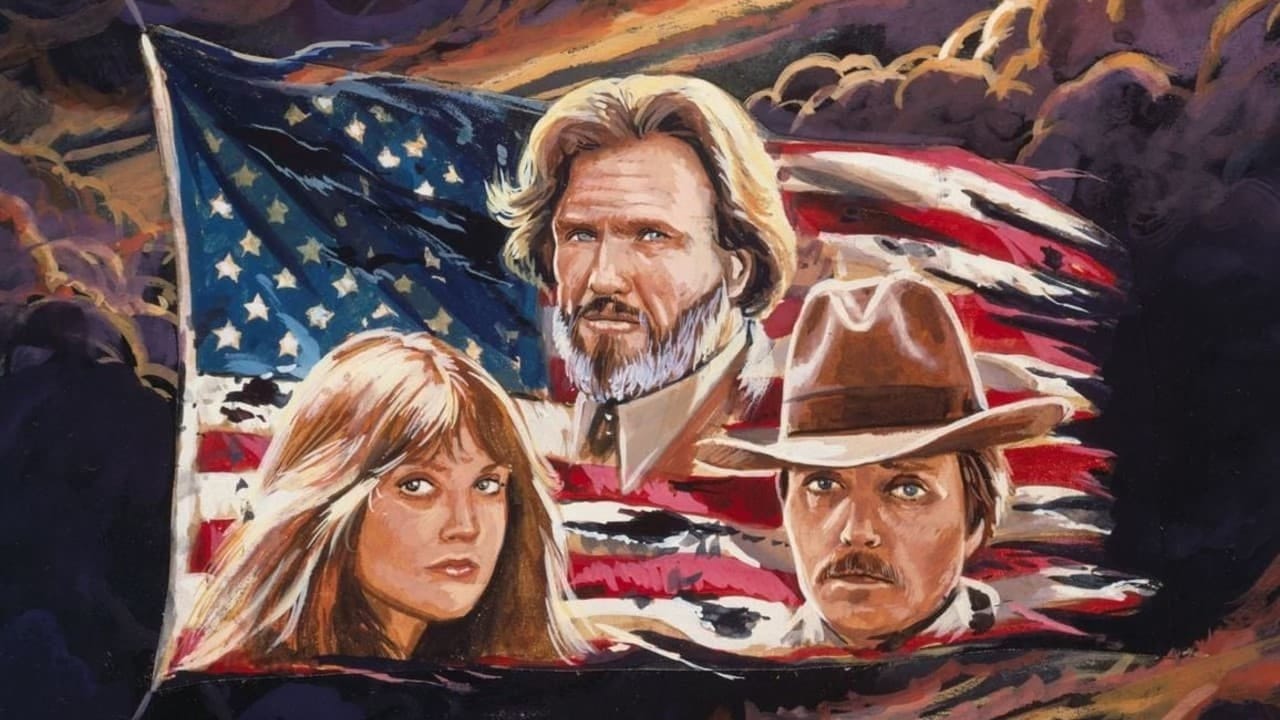

Even George Lucas had entered the decade with a guerrilla spirit, declaring early on that “the studio system is dead. It died… when the corporations took over and the studio heads suddenly became agents and lawyers and accountants. The power is with the people now. The workers have the means of production!” His THX 1138, which took down Zoetrope, was essentially an American art film. By the end of the decade, he had made Star Wars.

Some directors, like Peter Bogdanovich, stubbornly refused to compromise their integrity and failed ever again to make movies that bore cultural influence. As the ‘70s drew to a close, one of the decade’s most successful directors seemed destined for the same fate…

At the time, no one, least of all the man himself, would have expected Martin Scorsese to end up as the era’s great survivor, the Grand Old Man of cinema.

Much like Spielberg, Scorsese is portrayed throughout the book as an anxious, twitching wreck, “beset by superstitions” and quick to lose confidence. Like the protagonists of his films, he is shadowed by darkness, a self-destructive streak that manifests in an increasingly devastating coke addiction and culminates in a near-death experience in 1978.

Yet he possesses a mule-like stubbornness, an unyielding commitment to making films his own way. For Scorsese, Biskind suggests, there simply was no other way. Once, George Lucas poked his head into the editing room while Scorsese was making New York, New York (1977). Lucas suggested that Scorsese could “gross an additional $10 million if De Niro and Minnelli walked off into the sunset a happy couple.” Biskind quotes Scorsese: “When I heard him say that, I knew I was doomed, that I would not make it in this business, that I cannot make entertainment pictures, I cannot be a director of Hollywood films […] Cause I knew I wasn’t going to do it. I knew that what the two characters had gone through in that film, I had gone through in my own life, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to face myself or them if Bob and Liza were to go off together.”

As the meteoric success of Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976) gave way to the flops of New York, New York (1977) and The King of Comedy (1982) (sandwiched by Raging Bull (1980), framed by Biskind as the closing bookend of the New Hollywood era), Scorsese faced a choice. “I had to make up my mind whether I really wanted to continue making films,” he told Biskind. “There was such negativity that you might as well stop. So what do you do? Stay down dead? No. I realized then, you can’t let the system crush your spirit. I really did want to continue making pictures. I’m a director, I’ll make a low-budget picture, After Hours. I’m going to try to be a pro and start all over again.”

Scorsese, in other words, chose to fight. It’s a rare hint of triumph in the book’s otherwise mournful closing sections. Nearly all the directors mentioned experience a personal or professional nadir. The colossal flop that was Deer Hunter director Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), which lost an eye-watering $40 million-plus, empowered studios like Paramount to deliver the coup de grace. As studio executives reconsolidated their power, they had scores to settle. “The new celebrity executives were slow to forgive directors who had treated them badly,” says Biskind. “The ‘80s were payback time.”

Biskind paints a dark picture of post-New Hollywood cinema, portraying it as an artistic wasteland where mighty studios, packed with overbearing executives with strict quotas, conduct journeyman directors to force committee-made, brain-calming, profit-focused “crash-and-burn” content down consumers who have been trained to reject anything with more flavour.

Before the book closes with a touching account of Hal Ashby’s death from cancer, it’s left to Robert Altman to deliver the final quote:

“It’s disastrous for the film industry, disastrous for film art. I have no optimism whatsoever.”

The New Hollywood movement may be over, but reports of its leaders’ demise were exaggerated.

Many figures Biskind dismissed as out of the game in 1998 have since launched triumphant late-career runs. Scorsese, of course, has remained an enduring presence, Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2017), The Card Counter (2021), and Master Gardener (2022) are some of the best works of his career, William Friedkin briefly rediscovered his touch in the 2000s with Bug (2006) and Killer Joe (2011), and Terrence Malick successfully returned to the directors’ chair in 1998 (Malick, Scorsese and Schrader are all working on their next films). Meanwhile, Coppola returns this year with Megalopolis – a longstanding passion project made outside the studio system. True to form, the financial stakes are eye-watering – Coppola is said to have spent north of $120m of his own money on the production.

Yet one swallow (or two, or three) does not make a summer, and outside the individual success of certain filmmakers, Biskind’s systemic analysis still rings uncomfortably true. In fact, given the blockbuster trends of the past decade, it’s hard not to read Biskind’s despairing account of ‘90s filmmaking as a cruel joke. 1999, the year after Easy Riders, Raging Bulls was published, saw the release of The Matrix, Fight Club, Magnolia, Being John Malkovich, The Sixth Sense, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Eyes Wide Shut, Three Kings and Election, among others.

In hindsight, ‘90s Hollywood feels closer to the heights of the ‘70s than it does to today. Just as the ‘70s represented a cultural pushback against the play-it-safe studio trends of the ‘50s, so the ‘90s can be seen as a pushback against the style of corporate moviemaking that Biskind bemoaned as dominating the ‘80s (Quentin Tarantino has argued something similar).

It can be tempting, then, to try and map the early ‘70s and ‘90s positions to today—to equate the creatively bankrupt franchise era with the deluge of big-budget postwar studio fare in the ‘50s and early ’60s or the “crash-and-burn” content Biskind argues was delivered throughout the ‘80s. Perhaps there are already signs that audiences are ready for something new—Deadpool and Wolverine aside, Marvel has struggled to reclaim the cultural dominance it held in 2019, and last year saw ‘only’ two superhero films in the top ten worldwide box office (compared to six in 2018).

Even if we accept growing audience fatigue with franchise filmmaking (an assertion born as much from hope as reality), Biskind’s account of the New Hollywood era reads more like a cautionary tale than a case for optimism. One of his central contentions is that a lasting independent film movement requires fertile cultural soil to succeed. Given five minutes, most movie fans could rattle off a list of American directors working today whose output builds on the independent spirit of the ‘70s. However, “without a counterculture to nourish them,” Biskind writes, would-be-auteurs are “independent in name only, always at risk of being gobbled up and corrupted by the studios.” Barry Jenkins and Chloé Zhao might agree.

What a healthy 21st-century counterculture could look like is a topic for another essay. For now, I’ll end with two related thoughts.

First, it’s striking how films like The Godfather and The French Connection were initially viewed by their creators as compromises of their auteurist vision. Few would dismiss these films similarly today. The lesson? Time reappraises. It is still possible to create transcendent art within the constraints of a system one resents.

Second, consider some of the best films of the New Hollywood era: The Godfather II, Easy Rider, Taxi Driver, The French Connection, All the President’s Men, Shampoo, The Conversation. All were set either contemporaneously or within ten/twenty years of release. Now look at the recent output of today’s established American auteurs like Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Scorsese and Wes Anderson — it’s hard to think of a film set in the 21st century. Without, in Biskind’s words, a “nourishing” cultural movement, these directors seem compelled to retreat to history.

Perhaps, then, a new independent cinema, capable of igniting a broader cultural shift, needs to bravely confront the present.

Until then, filmmakers and cinephiles alike may continue to find themselves yearning for the past.

If you enjoyed what you’ve just read, you might also like this essay exploring the cinematic vision of James Gray, a ‘90s filmmaker who self-consciously styles himself on the New Hollywood model.

If you didn’t like what you’ve just read, what are you still doing here!

Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes in this essay are taken from Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.

I began my film industry career in 1969 and will begin my 56th year in June, 2025. I have worked in distribution, exhibition, marketing, advertising, and today in communications and business development. I lived and worked in the decades of Peter Biskind’s fine book. For me, it has been and continues to be a wild ride.

It was young film school trained directors who had learned a new film culture from mainly European auteurs who gave Hollywood its 1970s expansion . Now 250,000 film and TV students graduate every year and they could give a similar boost to film culture but they have no access to agents, producers , streamers or funding . There is so much potential going to waste because the system is totally out of date . Hollywood is dying ; it adapted to sound, colour , 3D , and was almost killed off by TV . But young directors saved it . That won’t happen now.