James Gray Has Something to Say

The director of Ad Astra, Armageddon Time and Little Odessa is fighting for the future of filmmaking

“My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impressions of nature.”

— Edward Hopper; Notes on Painting

Interviews with filmmakers can be a mixed bag.

Generally tied to the release of a new movie, they tend to suffer from a condensed format, generic questioning, and a rote series of talking points. You can often infer from the cautious restraint of the interviewee’s responses the warm, salty breath of the film’s financiers diffusing down their necks.

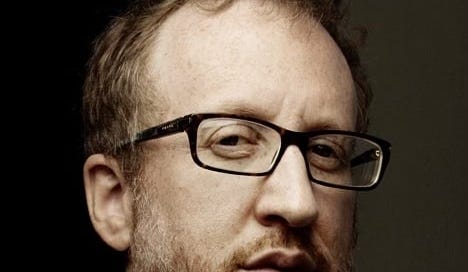

It was refreshing, then, to stumble upon the interviews of the director James Gray.

Candid, introspective and, whisper it quietly, insightful, his musings on the narcissism of the filmmaker, the supremacy of the superhero, the myth of the lone genius, the sacrifice of the artist, and more have genuinely influenced the way I think about art and THE MOVIES.

Since the release of his 1994 Tim Roth-led crime film Little Odessa, Gray has become renowned for his understated, personal, character-driven filmmaking, a style inspired by the New Hollywood wave of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

Praised by Scorsese and beloved in France, Gray’s work hasn't reached the public acclaim of contemporaries like Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson. However, within cinephile circles, it is held in similar regard. The average movie-goer is likely most familiar with him via his Brad Pitt-starring space epic Ad Astra (2019), which is probably the most austere possible version of a film featuring an exploding space station, moon pirates, and a rabid astronaut monkey.

Gray is a passionate advocate for cinema as an art form, declaring: “I’m not a religious person, because my religion is the cinema (…) it makes me feel more connected to the species.”1

If cinema is his religion, then his movies are his forms of penance; his baring of the soul. For Gray, filmmaking is not a profession, but a confession. The artist's role is “not to be autobiographical, but to be personal. What you do have is you have yourself to put into the film in as layered and honest a way as you can."2

Moviemaking, then, is “a very selfish, narcissistic endeavour.”3 The artist’s role isn’t to give the audience what it wants, or even what it needs. It is to reveal who the artist truly is; what they truly see:

“To be willing to hear that your most intimate impressions have been conveyed on the screen. That is our job. It is our job to take that risk. If we don’t take that risk, we may as well be investment bankers.”4

For an artist to expose who they are, they must accept that it may not be something the world will like. Anything short of that is, ultimately, a compromise, a fiction. Unless an artist is putting “the side that [they] are least comfortable with on the screen,” they are “not revealing an unsafe truth.”5

And what if people hate that truth? This, Gray notes with resigned acceptance, is the ultimate sacrifice of the artist. “You have to essentially take a risk and express yourself as personally as you can. And some people will hate it.”6

Failure, then, is an inevitable part of the process: “Most of the times, let’s be honest, most of the times you are met with failure. That is something you have to accept (…) So at some point you have to kind of be willing to break out and try do new things.”7

Gray dismisses the idea that films should merely reflect or reinforce the viewer’s pre-existing beliefs about themselves. Art is a process; it is about questions, not answers. It “communicates the idea of our search for our identity. That’s really at the core of really anything of value I think. What does it mean to be a person?”8

From this definition of art springs a revulsion at the idea that films should be “morally correct.” For Gray, it is the prerogative of the viewer to dislike the work, but to reduce one’s response to a film to a simple moral calculus is to lose touch with the very point of art:

“If you start creating rules in which I can tell the story of myself but it has to be through this morally correct lens, let me ask you something: what would happen if 50 or 100 years from now, don’t you think the sense of what is moral or ethical will change? And then what? And then what? What I think is incumbent upon the viewer, the reader, anything, any artform, is to allow the work in first and foremost as a work of emotional expression (…) It is not about boiling it down to what is morally correct. You cannot do that because that is not a fixed object. There is no such thing.”9

Art, then, is not a one-way process. Just as the artist has an obligation to convey their “most intimate impressions,” we, as the viewer, owe the artist what the writer George Eliot called “the extension of our sympathies.” It is, Gray argues, “incumbent on us to struggle and try to find the humanity in others.”10

Gray’s unashamedly hierarchical perspective may sound highfalutin to some, but when it comes to the nuts and bolts of filmmaking, his worldview takes a distinctly egalitarian lilt.

Art is sacred, yes, but the creation process is not. It’s a grind, a collaboration, a craft. Ultimately, “you only become good at what you do through repetition.”11 Even the Beatles, one of Gray’s favourite bands, stunk at the beginning: “When they left Liverpool for Hamburg, they were a group of motley musicians. 10,000 hours later, they came back and they were the Beatles.”12

Progress comes from perspiration, not inspiration: “Freedom is overrated: there is no art without discipline.”13

Gray dismisses the “genius myth,” the idea that a sole visionary is responsible for producing great art, as “bogus” and a “very dangerous” idea.14 No, art is collaborative, iterative:

“Mozart needed his sister. Lennon needed McCartney. Always a collaborative experience making a film. On each movie you have a different set of collaborators…that’s the thing that allows you to do something that’s of value.”15

Does this mean that the auteur theory, the much-debated idea that directors are the ‘authors’ of their films, is misguided? On this, Gray demurs. Films are collaborative exercises, yes, but ultimately “most terrific pictures are the vision of one person from beginning to end.”16

Lurking beneath Gray’s impassioned defence of the art of filmmaking is his rejection of the ‘Cinema as Content’ model that has consumed the modern movie industry.

He talks about the value of films as a self-contained medium, citing the power of The Godfather, for example, which is “even at 3 hours (…) a narrative juggernaut. It has like one basic concept: the transfer of power from father to son. And the thing is like a locomotive that plunges its way through the centre of your chest.” 17

As one may expect from a student of Scorsese, Gray’s view on superhero movies is nuanced but ultimately dismissive. They have their place (he is a fan of Tim Burton’s Batman Returns), but a culture solely consuming saccharine, factory-ordered content trains itself to reject anything more nutritious:

“If you give somebody a McDonald's hamburger to eat every day and you say, ‘here's another Big Mac and here's another Big Mac’ (…) and then I give you halibut sushi. Your reaction is not, ‘oh, the halibut sushi is great’. Your reaction is, ‘what the hell is this?’ The whole system has been primed to make sure that you accept only a superhero movie. So the audience doesn't know what the fuck to make of another kind of movie.”18

In Gray’s view, studios force-feeding their audiences a single kind of movie fulfils a short-term financial purpose but is ultimately an act of self-harm. Over time, it begins to “get a large segment of the population out of the habit of going to the movies, and then you begin to eliminate the importance of movies culturally.”19

The solution, Gray argues, is to inject a dose of artistic vision into the production process; to empower divisions within big-money studios to take venture-style bets on art films free from the usual financial calculus imposed on studio decision-making. This, he argues, will help reinvigorate “broad-based” engagement with movies as a cultural force.

There is a sadness to Gray’s interviews, a resigned, tacit acceptance that his golden mode of filmmaking is increasingly a mirage, a spectre within an industry that is being transformed beyond recognition.

And yet, out of this despair emerges a certain defiance; a determination. Gray has committed to continue making films for “as long I possibly can. I find that there’s something very beautiful and immediate about that medium.”20 He is reportedly working on his next film, Mayday, about the young JFK.

Hopefully, the film will be a huge success. Even if it isn’t, Gray’s not going anywhere:

“most of the times, you know, I have been met with terrible failure.

And yet not.

I’m still here.”21

Director James Gray discusses Ad Astra (The Director’s Cut)

James Gray: A Conversation (Austin Film Festival)

Director James Gray discusses Ad Astra (The Director’s Cut)

Director James Gray discusses Ad Astra (The Director’s Cut)

Director James Gray discusses Ad Astra (The Director’s Cut)

James Gray (WTF with Marc Maron)

Really appreciate this way of looking at art - will go on a James Gray binge tomorrow.

What excites me about him is that he seems to put great emphasis on narrative. I think the more I delve into my novel (right now anyway!), the more I feel that true storytelling is the most wonderful thing. Story as a way of revealing truth, I suppose?

I think it's why a film like Saltburn didn't speak to me. It felt like a collection of things, with no struts to support - a bit like finding yourself tangled in a bed sheet!

I watched Memories of a Murder today (ill in bed so just binging), but goddamn is that great storytelling. Sterling character development. Very funny. Very beautiful. A well paced yarn. And that ending! By ye Gods!

Yes, yes, yes, yes and yes. First time I'm seeing all of this from James Gray but I'm loving it all. Great piece Ed!