Welcome to the 36 new subscribers who’ve joined since my last post, a 3,000-word missive on movie history that was, in a tactical masterstroke, released on US election day... Here's the link for those who missed it: What Was in the Water in 1999?

Today's essay unpacks a pernicious trend in modern movie discourse...Something strange is happening to how we talk about movies.

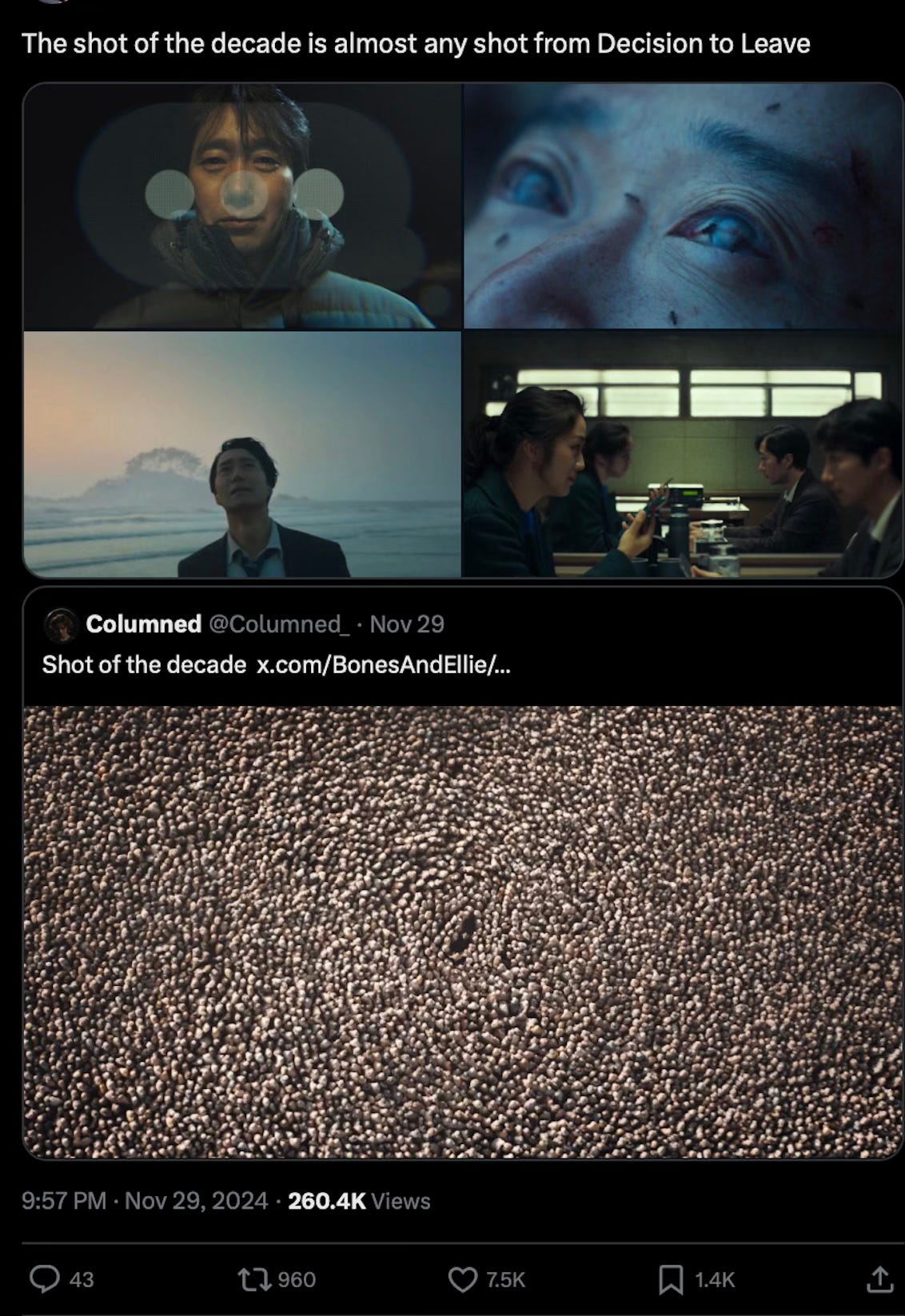

Our social media feeds are bloated with “One. Perfect. Shot.” images like this:

These perfectly composed isolated frames, frozen in time and stripped of context, have become one of our primary ways of appreciating cinema.

Between starting this piece and publishing it, there’s been a whole pocket discourse on Twitter/X about the "shot of the decade,” a conversation that has been reduced to “the prettiest frame of the decade.”

I’m a basic boi at heart. I’m as much a sucker for these images as anyone. But even as I salivate, I’ve always had a nagging sense that something about this feels somehow… cheap.

My reservations aren’t just due to a nebulous sense of ill-placed artistic snobbery (although I’m sure that’s in the mix). Beautiful though these frames are, out of context they feel like cinematic snack food — digestible morsels that slip down the gullet without providing sustenance. I fear that the more we consume them, the more we risk forever altering our palette.

It’s time to talk about wallpaperism.

Ever had a family member corner you with a crappy holiday photo of some foreign architecture? Idly glanced at a hotel lobby print of the Mona Lisa? Watched a recording of a stage production?

I’m guessing it didn’t have the impact of the real thing.

A mere reproduction of an art form will never capture the original’s magic. It’s always going to be an approximation, a Xerox. The creative spark will be lost in translation.

This argument was made nearly 50 years ago in an eerily prescient 90-page missive from one of cinema’s most influential directors.1

Robert Bresson’s theory of film, articulated in his Notes on the Cinematographer, is organised around a simple premise: Cinema should not imitate other art.

“The truth” of cinema, Bresson argues, “cannot be the truth of theatre, not the truth of the novel, nor the truth of painting.” To be truly powerful, truly alive, cinema must play to its own strengths: “It is in its pure form that an art hits hard.”

“Pure Cinema” sounds kind of badass, but what is it? What makes cinema… cinema?

Well, unlike theatre, unlike paintings, unlike novels, movies can smash sounds and images against each other. A great film, says Bresson, can “bring together things that have as yet never been brought together and did not seem predisposed to be so.”

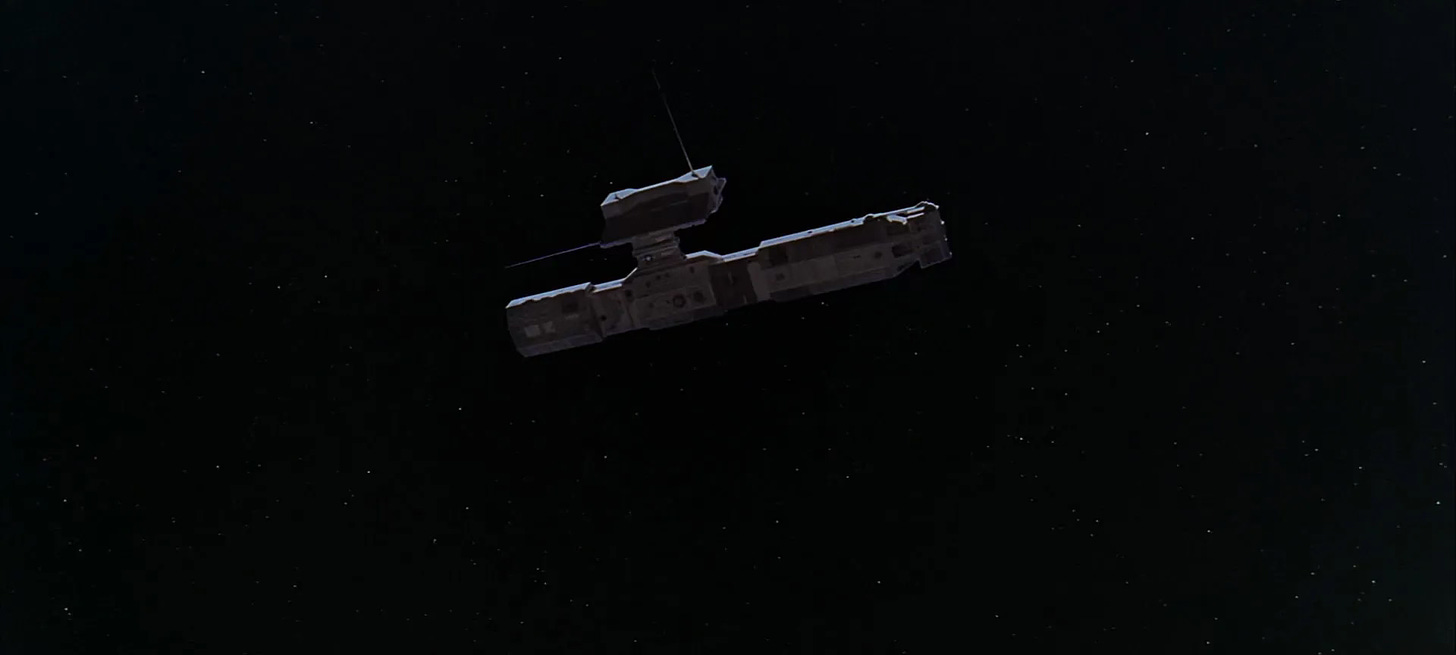

Cinema is the only art form that can go from here:

To here:

Both of these frames are cool in isolation. Together, they become something else entirely. Their life, their meaning, lies in the space between them. The cosmological, technological, and chronological scope of Kubrick’s story made flesh.

As Walter Murch once said, cinema is a Frankenstein’s monster of an art form, stitched together from a thousand dead parts. Scenes are filmed out of sync and pieced together from several takes, pick-ups are shot separately, dialogue is post-recorded in ADR, and music and sound effects are added post-hoc. Smash these different parts against each other, and suddenly, alchemy. Life.

The truth of cinema lies not in isolated images and sounds but in how they relate to one another.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m not arguing against visual beauty. Breathtaking images are the bread and butter of the medium. I mean, look at the below shots from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941). But notice how, together and in context, these striking images speak to something higher, signalling Kane’s fleeting power, hubris, and impending downfall.:

Or, to return to Blade Runner 2049 (Villeneuve’s masterpiece, comfortably superior to both Dunes), while the image that sits atop Lex Fridman’s Twitter page is cool, its real power comes from its context: the stark contrast with the film’s other monochromatic palettes, the patient, methodical long takes Villeneuve uses to cultivate a sense of isolation and ecological devastation, and the wry glimmer of hope that emerges shortly thereafter:

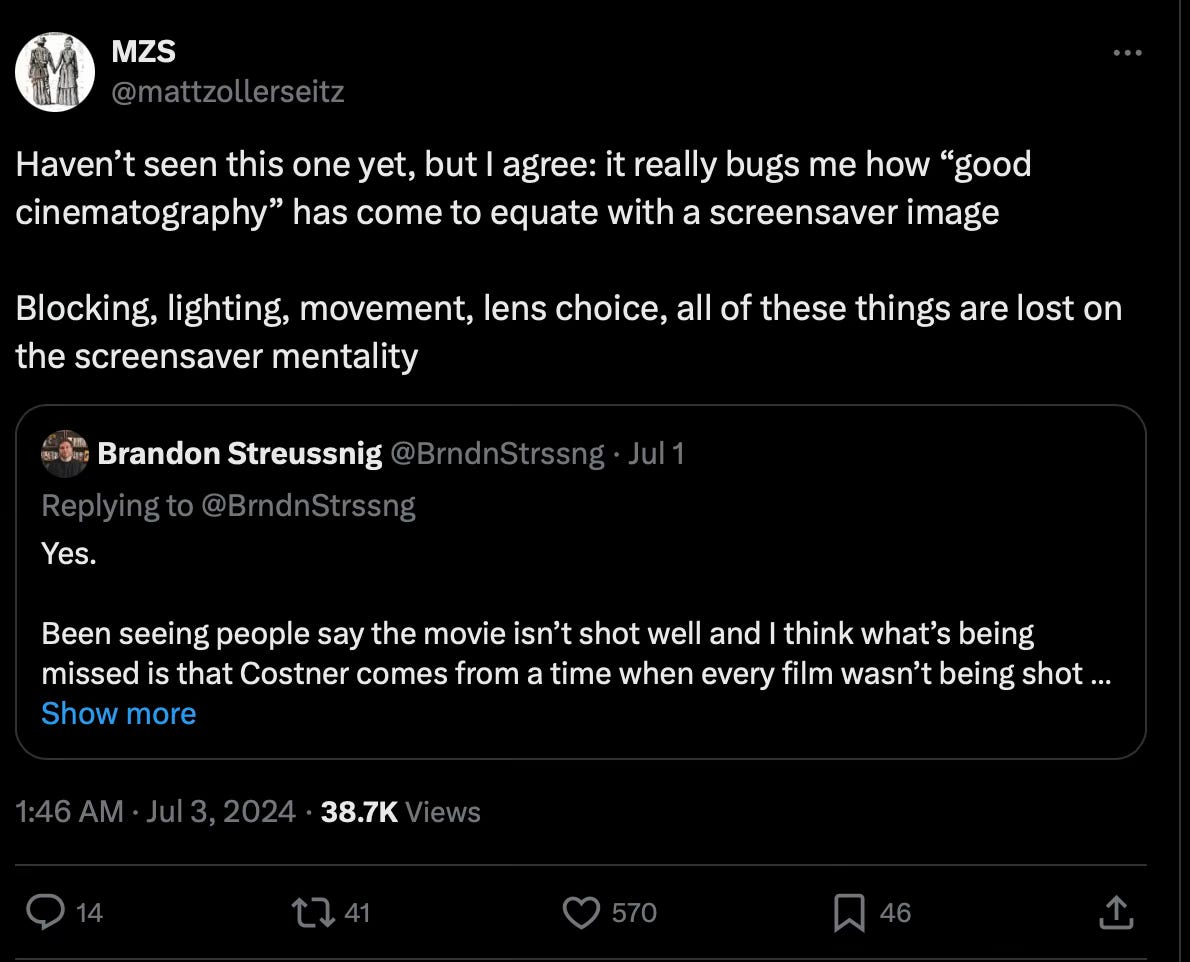

“Nothing more inelegant and ineffective than an art conceived in another art’s form,” writes Bresson. Our obsession with still frames devoid of context means we are stripping away what makes movies their own art form and not just watered-down approximations of better ones.

So what if people want to enjoy their pretty pictures? Does any of this actually matter?

Well… no. Touch grass and all that.

But for film lovers like us, and for anyone who decries the Marvelisation of cinema, the decline of intelligent movies, blah blah blah, this really does matter.

The more we think of cinema as a series of hermetic, self-contained images that look great when we fire up our Macbook, the further we drift away from what makes the medium such an emotional, intellectual and artistic juggernaut.

If the lesson tomorrow’s filmmakers draw from great movies like Blade Runner 2049 is “pretty image = good movie,” then future iterations are doomed to become hollowed-out approximations of the real thing, all-you-can-eat buffets of soulless beauty.

“Your film’s beauty will not be in the images (postcardism),” Bresson writes, “but in the ineffable that they will disengage.”

By focusing on isolated images, we are replacing the ineffable with the Instagrammable.

If that’s not a loss, I don’t know what is.

If you enjoyed reading and would like to support my work, please consider buying me a ‘coffee…’

If you didn’t enjoy it - what are you still doing here!

Great piece! Here’s a good way to know if you’re doing pure Cinema: translate the film into another medium and see how much is lost. To me, the quintessential examples are the Sergio Leone Westerns.

-They cannot be made as books because the story and dialogue are minimal.

-They cannot be played in theater - because Leone needs your attention directed where he tells you (for the shot to work).

-They cannot be made into comic books - because the music and synchronous rhythms are essential parts of the scenes.

They can only be films. Pure Cinema.

Cinema often lives between two images. Between Lawrence of Arabia admiring the Sheik's clothes gifted to him in the reflection of his knife, and where he looks down in horror at the same knife, now caked in blood after a senseless slaughter, lives a cinematic story about a complex, conflicted and fascinating man.