Ahoy there to all to the new subscribers who've jumped aboard since my last post, which took a few pot shots at the "style over substance" critique. Good to have you here!

These essays take time. I want to keep them free for now, but if you've enjoyed my work and would like to support it, I've added a Buy Me a Coffee link to the end of this post. I enjoy writing in coffee shops, so you would quite literally be fuelling my next piece! You’ve probably seen the books vs screens meme:

The implication is clear. Reading a book inflames the imagination, while watching a screen smothers it.

It’s a compelling idea. It’s also bollocks.

People should read way more than they currently do. There’s an abundance of slop on our screens, and we waste an inordinate amount of time consuming it. If people read more average books rather than watching average TV, that would be a net positive.

But I’m not talking about slop, I’m talking about cinema. Film is an art form, and, like any great art, it can ignite the imagination.

The more you understand how cinema works, the more you get out of it. A basic level of literacy makes a material difference (a pretty good articulation of what I’m trying to do with this Substack).

So, the question is how? How does cinema engage the imagination?

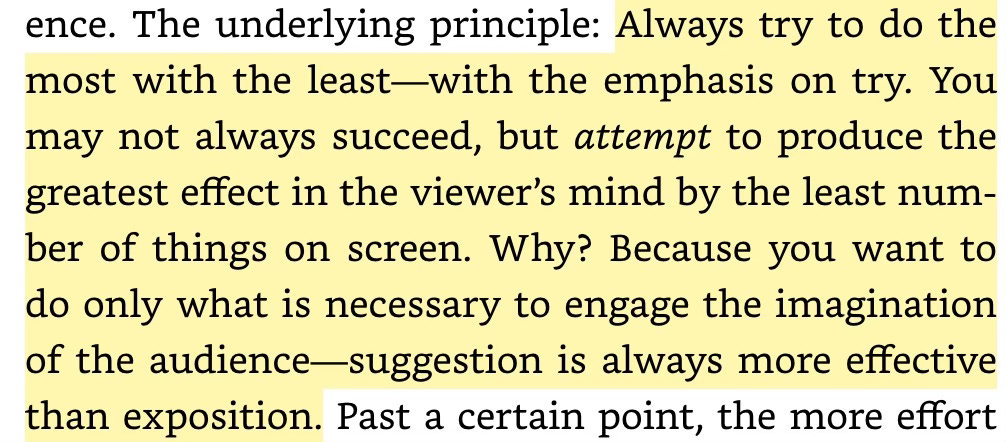

The more I read interviews and books by filmmakers, the more that economy, the ability to do more with less, emerges as the golden rule of cinema.

Here’s Apocalypse Now editor Walter Murch:

And French legend Robert Bresson:

And Indian icon Satyajit Ray:

To spark imagination, a film must leave it with room to roam. To overexplain, to do in a word what can be done in a visual, to do in a scene what can be done in a shot, is to put guardrails around the mind, forcing it cookie-cutter-style into a predefined shape.

“When less than everything has been said about a subject, you can still think on further,” says Andrei Tarkovsky. “The alternative is for the audience to be presented with a final deduction, for no effort on their part, and that is not what they need. What can it mean to them when they have not shared with the author the misery and joy of bringing an image into being?”

Take the below scene from PTA’s There Will Be Blood. The conversation’s gutwrenching effect emerges from what’s implied rather than what’s spelt out for us. We have to do some of the work. We have to imagine.

I used to equate economy with asceticism. It struck me as a stuffy argument against the bombastic cinema of Spielberg or Nolan or Cameron or any other mainstream blockbuster. The kind of film-school-style sneering that dismisses popular entertainment. I was so wrong. Economical storytelling is as fundamental to these films as it is to a slow-paced arthouse flick. I challenge anyone to find a more effective 20 seconds of blockbuster storytelling than the opening of this scene from Jurassic Park:

The point is that economical storytelling does not mean telling ‘less’ story or making a film more boring. It means staging things in a way that leaves space for the viewer’s imagination to, in the words of Photoplay editor James Quirk, “hear things which [the filmmakers] suggest — the murmurs of a summer night, the pounding of the surf, the sigh of the wind in the trees, the babel of crowded streets.”

This is why the (admittedly overused) refrain “film is a visual medium” is more than just an empty truism. An image (or series of images) will usually provoke the imagination more than dialogue will, leaving us to consider the poetic or emotional truth that the images represent.

It’s also (yet another) reason for the sanctity of the theatrical experience. Put simply, it’s harder to inflame the imagination from the comfort of your sofa. If you are quickly checking your phone, grabbing a Coke, or getting distracted by the cat cleaning itself, then you are not engaging with the movie. The process goes from creative to passive.

So, to return to where we started, yes, watching a great movie is a creative act.

It’s not just incumbent on the filmmaker to do more with less. It’s on us to engage with what we’re given, to approach a movie as a participant, not a consumer. “The method where by the artist obliges the audience to build the separate parts into a whole, and to think on, further than has been stated, is the only one that puts the audience on a par with the artist in their perception of the film,” writes Tarkovsky. “Only that kind of reciprocity is worthy of artistic practice.” Absolutely.

If you enjoyed reading this article and would like to support my work, please consider buying me a “coffee” to help fuel my next piece.

If you didn’t enjoy it… what are you still doing here! Go outside!

This immediately went into my archive for reference. A lot of people are writing on here about movies; I like that you are writing about cinema, and how the medium affects the viewer’s brain.

Big fan of show don't tell. I want to be challenged when watching a movie and piecing everything together myself with little nudges from the filmmaker is a lot of fun. How good is that Jurassic Park setup!