*📣 SPOILER KLAXON 🔊* for multiple Scorsese films but NOT for Killers of the Flower Moon, which I wrote about here.

I. The Tragedy

“I borrow money from you, because you're the only jerk-off around here who I can borrow money from without payin' back, right?”

— Johnny Boy; Mean Streets (1973)

Johnny Boy is a loose wire.

Played with a fluid, lanky bounce and easy charisma by a young Robert De Niro, he spends the majority of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) hurling insults at minor mobsters, brawling with street-level crooks, and, most dangerously, reneging on debts with local loan sharks.

His childhood friend Charlie (a restrained Harvey Keitel), the nephew of a powerful Little Italy mafioso, has poured a significant amount of social capital into protecting Johnny Boy, including against the growing frustration of the serpentine Michael, one of the loan sharks to whom Johnny Boy owes money.

Caught between Michael’s rapidly disintegrating patience and Johnny Boy’s wild erraticism, Charlie becomes increasingly desperate in his attempts to persuade Johnny Boy to smarten up.

Charlie manages to persuade Michael to cut down the outstanding debt. He loans Johnny Boy some money together with a stark warning, “Don’t show up tonight, we’ll see what happens to you.”

It briefly appears that Johnny Boy has realized the severity of the situation.

No such luck.

Next scene, he defiantly reneges on his debt and openly disrespects Michael to his face.

By the end of the night, he will be dead.

II. The Ultimatum

“Listen, Frank. Things have gotten out of hand with our friend again. And some people are having serious problems with him. And it's at a point where you're gonna have to talk to him and tell him: It's what it is.”

— Russell Buffelino; The Irishman (2019)

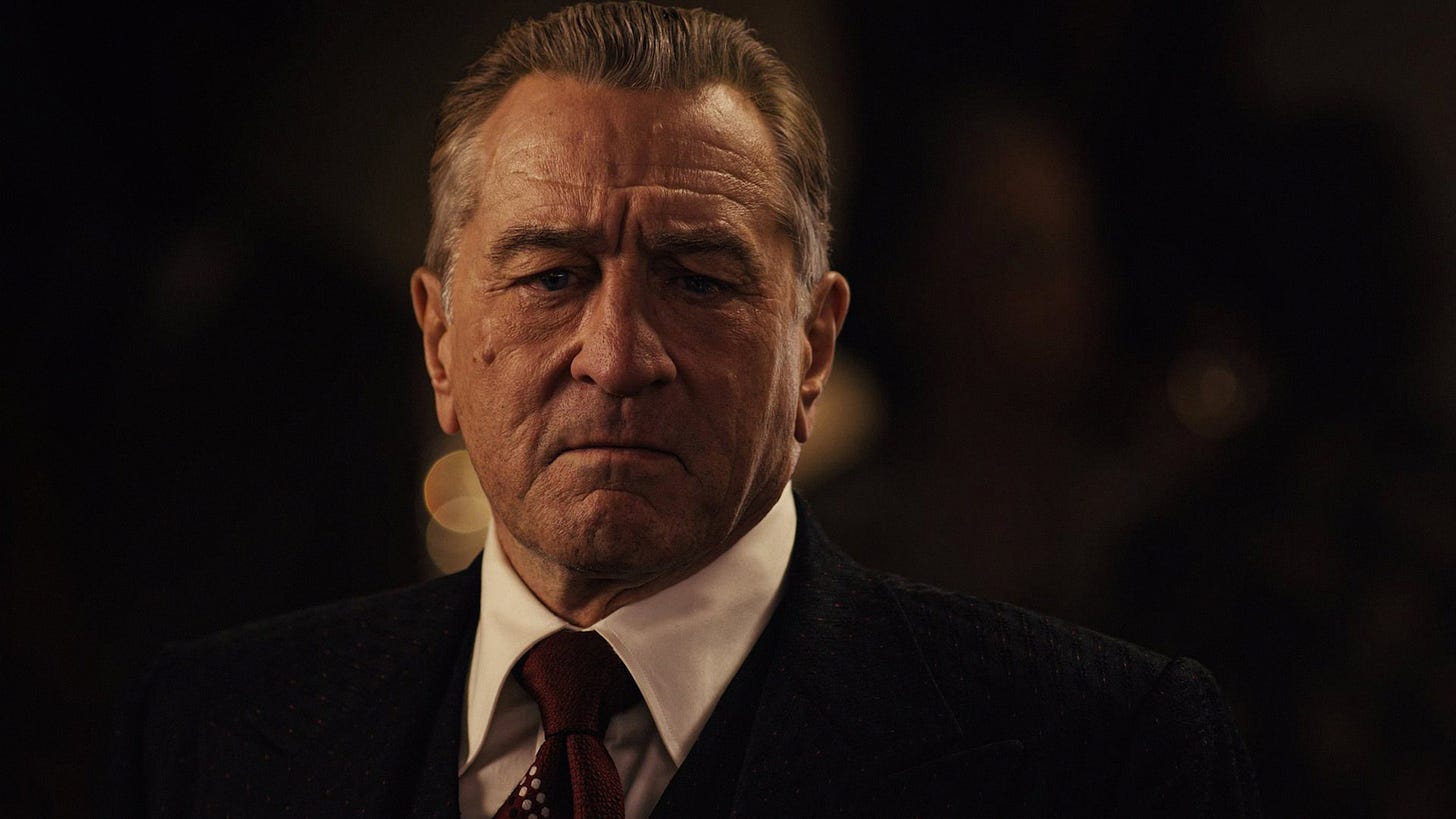

Fast forward 46 years to Scorsese’s magisterial mob epic The Irishman (2019), also starring Robert De Niro.

This time, the roles are reversed. De Niro, playing stoic, granite-like hitman Frank Sheeran, assumes the role of the understated, conflicted gangster, and the man refusing to listen is ex-union boss Jimmy Hoffa, played with characteristic bombast by Al Pacino.

Hoffa, drunk on the power and influence conferred by his union connections, has been playing fast and loose with the imprimatur bestowed on him by the Pennsylvania mafia. So fast and loose, in fact, that the mafia has decided to tighten the leash.

Frank is the man in the middle: although a close friend, bodyguard, and confidant of Hoffa, he ultimately owes his career and life to the mob.

In one of Scorsese’s best scenes, Frank is tasked by his mafioso mentor with providing Hoffa an ultimatum: moderate your behavior or face the consequences.

He tries to impress on Hoffa the severity of the situation using a brilliant bit of mob vernacular: “it’s what it is.”

Pacino allows the hint of doubt to creep across Hoffa’s face but is ultimately dismissive. “They wouldn’t dare.”

The clock is ticking. Within two years, he will be dead.

III. The Delusion

“Loneliness has followed me my whole life. Everywhere. In bars, in cars, sidewalks, stores, everywhere. There’s no escape. I’m God’s lonely man.”

— Travis Bickle; Taxi Driver (1976)

There is, perversely, a common ground when two people fundamentally disagree. The rules of engagement are clear: one person thinks X, and the other thinks Y.

For Hoffa and Johnny Boy, it’s different. There’s no argument per se. There’s no maneuvering or counter-maneuvering. Instead, there’s a fundamentally different understanding of reality.

Much of Scorsese’s work is defined by this absence of “real” conversation. Characters speak to and at, but rarely with, each other. They hear not what is said but what they need to believe.

Scorsese has claimed that loneliness is the handmaiden of his love of cinema. His project as a whole can be interpreted as the canonization of modern male isolation. By populating his films with characters who cannot accept stark reality, he is revealing true loneliness’ inevitable endpoint. Without anyone to anchor them to reality, they delude themselves into concocting their own.

Take Rupert Pupkin, the wonderfully named protagonist of Scorsese’s maligned-at-the-time but increasingly prescient The King of Comedy (1982). Pupkin, an aspiring comedian, rejects repeated confrontations with his own mediocrity. Instead, he retreats into grandiose delusions, clinging to a belief in a personal reality where fame is inevitable.

Delusion destroys Jake LeMotta in Raging Bull (1980), a man so consumed by jealousy and rage that he is blind to the loyalty of his wife and brother. It brings down Sam ‘Ace’ Rothstein in Casino, a control freak who, in Sharon Stone’s Ginger, introduces an uncontrollable livewire into his carefully managed life despite her clear lack of affection.

The further Scorsese’s characters descend into their fictional reality, the harder it becomes for them to escape. This idea reaches its apotheosis in Shutter Island (2010), a film about a man who is so haunted by the dark truth of his past that he creates an entire imagined world to escape it.

IV. The Failure

"What kind of man makes a phone call like that?"

— Frank Sheeran; The Irishman (2019)

We've all experienced the frustration of failing to convey a crucial truth to someone who appears to be operating in a different reality. It’s unsettling, yes, but it’s also strangely disempowering. There’s a feeling of helplessness, an all too familiar twinge of inadequacy.

This is why, despite being a murderer who betrays his best friend, De Niro’s Frank in The Irishman is almost sympathetic. The “it’s what it is” scene boils down to a desperate man trying and failing to find a way to reach his friend.

But Scorsese doesn’t just present us with the gut punch of failure; he outright asks us: how culpable are we for its consequences? Are we responsible for the fallout when our warnings go unheeded?

His films dare to suggest that perhaps we are somehow complicit. This idea culminates in The Irishman, where Frank must pay for his inability to restrain Hoffa by being the man to deliver the killer blow. But we can also see it back in Mean Streets, with its haunting near-final shot of a desolate Charlie on his knees, reckoning with his failure.

In this sense, Scorsese’s films reflect his (well-documented) struggles with his religion. Try as he might, he is unable, or unwilling, to deliver us absolution.

V. The Warning

"You don't make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit and you know it."

— Charlie Cappa; Mean Streets (1973)

These deluded, unpredictable characters serve a narrative purpose. They are livewires, maniacs, catalysts for action. They provide their films with a propulsive unpredictability and fear factor that is inherently watchable (see, for example, Johnny Boy’s imperiously stylish entrance in Mean Streets).

But they also offer a warning.

By forcing us to spend time with, engage with, and sometimes sympathize with, these deluded men, Scorsese is hinting at something profoundly unsettling.

We like to think of ourselves as rational, logical, calm-headed individuals. But how often have we each been presented with information that challenges our worldview, that pierces our reality, and how often have we dismissed it?

Maybe we’re not always the ones trying to get the message through. Maybe we’re the ones not hearing the message.

If so, Scorsese’s warning is clear. Fail to listen; fail to acknowledge reality, and the consequences will come from the barrel of a gun.

This was a real pleasure to read, Ed! I don't know what it says about me, but I love the way Scorcese has charted "modern male isolation" over the years - perhaps it's because we're broody artistic types 😂 - definitely inspired to revisit some classic Scorcese now!

Maybe it's the Italian-American thing, but my Arthur Miller klaxon was going off - A View From the Bridge has a similar deluded protagonist Eddie Carbone, and its that delusion that ends up trapping everyone, such that when reality breaks through, it does so with a vengeance. Feels like a mega classical trope, no? The old Greek tragedy.

But, I loved this idea that you flesh out: that the single character's fictional reality isn't just about their self-delusion. It's that their delusion shapes the reality of those around them as well, a sort of societal poison that entraps everyone. That parallel you draw between Frank and Hoffa is just so perfect - their delusions are so symmetric! Reality forces Frank to make amends; reality forces Hoffa to pay the price. It's like the corruption of truth upsets the fabric of reality.

Wonderful writing and great subject matter, man. Loved the range. Loved the quotes. Loved the choice of those two bookended Bobby D pics!

Thanks for mentioning that there were no spoilers for KTFM at the top -- I still haven't seen it! That running time is making it hard for me 😬